Cristina Morozzi: And are we seeing the same thing in product design?

Gillo Dorfles: Patricia Urquiola, for example. She’s an excellent designer, but why does

she need to add those coloured superstructures? And Philippe Starck? Why has

he even gone so far as designing garden gnomes? It’s just an exaggerated wish

to “épater le bourgeois”.

Well, since you mention garden gnomes, it’s unavoidable that I must ask you about the evolution of kitsch, a subject on which – with your usual ability to see what’s happening before anyone else – you wrote an illuminating essay in 1967, the famous Il Kitsch– Antologia del Cattivo Gusto published by Mazzotta.

“Kitsch isn’t confined to a narrow field as it used to be. Today it’s part of everyone’s life. We can see that contemporary art has more or less deliberately adopted elements of kitsch, because there seems to be a widely felt need for a certain amount of cheap triviality. In the same way, there’s a worldwide interest in pop music. It all shows that the human race can’t get along, unless there’s always a proportion of kitsch in life, and as is very obvious, in fashion as well. Once upon a time it was to put gnomes in the garden, but now kitsch is everywhere; it’s a component of civilisation now, and that’s not entirely a bad thing.11”

Don’t you think that critics have to take some responsibility for always trying to get in the news, by espousing the most shocking thing they can think of? Haven’t they been a part of spreading and mythologising the excess that get bigger headlines, than things that are more ordinary and quiet? Could it be a slippery slope we won’t be able to climb back up?

No, it isn’t the critics’ fault. There’s a spectacular aspect of things that anyone involved in design spends at least 50% of their time thinking about. It relates to advertising what they do, and is crucially important for getting into the market. As for the idea of rigorous good taste, that was actually a way of selling products in 1950s advertising. Today, we’ve gone the opposite way. It’s a given for designers that form follows function, and depends on what can be made using particular materials, but to get your idea out there you have to sell it.

So the demiurge is the market?

“There are young people, quite a lot of them, who decide to be artists because they think it’s an easy way to fame and fortune. The decision to be a painter, a media star or just to be somebody on the international art scene, is linked to the idea of rapidly crowning your dreams with glory and wealth. This fantasy is justified by the physiology of contemporary art itself; what keeps it going is the market, with its echanisms and payoffs. In their quest for success, aspiring artists adapt to those market forces, the laws of supply and demand (12)”.

Gillo Dorfles, 2008.

But it seems to me there are some celebrations that make no criticism and go too far. I get the feeling that now, in product design too, there’s a tendency to create divas of design, sometimes in ways that have nothing to do with the real value of their work. This is due to the wider interest in design now, whereas before, you only found design in specialist magazines. There’s now an inability to discriminate, and an excessive arbitrariness in the way opinions are formed? In short, isn’t design being too easily mythologised? Is this happening so that design can be made more palatable to a wide audience that only wants celebrities? Why is it becoming harder and harder for the real facts to get through? Harder to say anything that isn’t just going along with the chorus?

Certain kinds of celebration are only another way of advertising products by hedonistic, venal means. I’m known for expressing my views openly, but I wouldn’t go out of my way to offend anyone on purpose, and there are things I think that I simply cannot say in public. Consider it a salutory form of self-censorship. Were I to say what I really think on this subject, I would already have been shot ten times or more! Even when I wrote Lacerti della memoria13. I left out important things that should have been said. Truth doesn’t belong to this world; we have to lie, day and night. Sometimes, I admit, I even make things up. I don’t actually like telling it straight;

I like to invent.

Perhaps, aided by your irreverent, witty pamphlet Conformisti, published in 1997, we can agree that today’s myth-making has little or nothing to do with ancestral myths.

“Myths have either faded or been replaced by delusions, and wild media ballyhoo about certain individuals, who in terms of their actual ethical, ideological and aesthetic worth, are completely insignificant. These meaningless new myths go along with even more pernicious, senseless rituals that have the sole function of making people conform.14”

Just as in the art world, so the product design world has its great untouchables: creatives about whom we dare not express the slightest negative or even doubtful opinion. Others are neglected or even shot down in flames. I wish I could mention names and surnames, but I’ll go along with you and censor myself. I could mention one architect (who shall remain nameless, much as I'd love to say who he is) who built a roof canopy beside the main railway station. A controversy was whipped up about it, and the architect became such a hate figure that he was forced to move away from the native city, where he lived and worked. The school of architecture of that city even assigned, as an appropriate topic for final thesis projects, the dismantling of his canopy.

Well, a lot depends on the personality of a designer, their ability to inspire confidence. Charisma. It’s as important today as it ever was. Every epoch has its own form of charisma, and today’s is all about putting on a show.

Could it be that the press has too much power? We often see sensational-looking prototypes that were clearly known right from the start to be almost impossible to put into production, only made to get publicity in magazines.

The press only has power because we allow it. As for the art market: if you take Mark Rothko or Robert Rauschenberg, for instance, is their work worth the billions it fetches? There isn’t a painter today whose work isn’t prey to market forces. The market even takes mediocre painters and invents their worth: someone like Damien Hirst, who understands how the market works and is very skilful at exploiting it. Being a skilled player in the market is crucial.

In the movies and show business it’s natural to create myths as part of the process, but is myth-making at work in product design too?

There’s always a need for myths but when the process becomes absurd, things that don’t deserve it are made into myths. We’re surrounded by fake myths. But there are also good myths. I think it’s a good idea, for instance, to put certain historic pieces of product design back into production. There’s some furniture that’s worth making a myth out of, such as Carlo Mollino’s or the Eames’s. For me, it’s good that Cassina recently put some of Franco Albini’s furniture back into production. Albini is one example of a designer who has been made posthumously into a myth, late in the day.

When I came to see you my plan was only to talk about design, but your ideas are so wide-ranging that we keep wandering off-topic. Can we get back to product design?

“A piece of product design is far more than just an object. That observation should be enough to tell us that when Husserl was talking about a ‘return to things’, he meant returning to a relationship with a world of things that are alive, and are not mere objects. ‘Thing’ in Italian is ‘cosa’ and when we’re deprived of our things, we’re like a turtle that’s lost the shell it lives in, its house, (‘casa’ in Italian).

Gillo Dorfles, 2008.

Gillo Dorfles, 2008.

The Italian words cosa and casa happen to be almost the same; our house (casa) is made up of our things (cose), and without the one or the other, we’d be naked, even more unbearable than having no clothes to wear. In an age like ours, divided between rationality and superstition, faith and mystification, fanaticism and agnosticism, the aesthetic sense of form that at other times often found its highest expression in supremely functional objects, often loses its focus now.

You can see this in many recent design objects that have abandoned some of what were formerly thought to be design’s essential characteristics. Instead, and Fulvio Carmagnola has written about this15 a new space-time concept is being expressed, which Carmagnola sees exemplifed in Ron Arad’s famous Bookworm bookcase, by Kartell, ‘in whose sheer perceptual presence there is nothing that might indicate with certainty the nature of what it actually is’.16”

So – what about things?

Human beings are hugely attached to objects. They need things they can be fond of. And diversification of these objects is an anthropological necessity; each person wants his or her own favourite items, and we all need talismans and fetishes. But those dolls, that are so popular now, are only a simplified version of what we need.

In your book Design Percorsi and Trascorsi17 you wrote: “For several years now we find ourselves at a memorable turning point in the field of industrial design, and generally in every field of design: if we look at some of the items invented by the two movements Memphis and Alchimia, we see that very often, they did not take any account of the relationship between form and function; they were mainly intended to amaze by means of formal innovations.

At first, the expressive vitality of these movements was greeted with extreme satisfaction; many of us were sick and tired, indeed nauseated by the monotony of the International Style, not only in architecture, but in everyday objects and furniture. In that situation I can claim to have been one of the first to reflect on how the positive work of Ettore Sottsass, and partly also Mendini, Pesce, and Branzi, had the courage to question the absoluteness of traditional design,especially that modelled on the patterns of German Functionalism (as in the typical objects produced by Braun)”

Twelve years have gone by since you wrote that, and it seems to me that although progressive changeability and an increasing variety of expression are inherent characteristics of product design, recently we’ve come to another significant turning point. In July 2008 the monthly British design magazine, Icon, published a league table of "ugly design objects" to mark the emergence of an aesthetic of the ugly, just as some time ago (1998) Mario Perniola had theorised in his essay Disgusti (Costa & Nolan). The pieces in this league table are completely different from the benevolence of classic kitsch; there’s something aggressive about them we hadn’t seen until lately. Top of the list were known and established designers like Fernando and Humberto Campana, who are also courted by art gallery owners.

Some designers like Fernando and Humberto Campana are interesting in their own way, and I support what they’re doing. I do think kitsch is reasserting itself, even though in ways that seem completely different from the characteristics it was possible to codify the first time around. People are attracted to anything unusual and unpleasant, and kitsch in all its expressions, even the crudest, has a consoling effect. Just think of how common it is in fashion: in that field, whatever’s trashy is greatly appreciated.

Every epoch has its own form of charisma, and today’s is all about putting on a show”Aesthetic value cannot any longer be entrusted exclusively to good taste; our axiological judgment cannot be separated from our emotional attitude. Perniola puts it like this: 'whilst in making judgments about taste, the cognitive dimension remains very important, as knowledge it is devoid of any real value where disgust is concerned, because the affective condition takes over.'

So why not admit a conclusion that is fairly alarming, but which I believe to be authentic: a great many situations that provoke the greatest disgust in us, beginning from the whole universe of kitsch and continuing with the tide of pulp publications, inane pop songs, and gaudy television spectaculars, are in fact the art of our time. It is perhaps only through the disgust they provoke in us that at some point in the immediate future, an effectively renewed taste will effluoresce (18)”

We’re seeing more and more exhibitions now of short-run product design and one-off pieces. There’s hardly an art exhibition these days that doesn’t have an artistic design exhibition tacked on to it. Many famous art gallery owners, such as Gagosian, who presented a one-man show of Marc Newson in his New York gallery in January 2007, have begun holding exhibitions of signed and numbered design objects, and more and more industrial designers are working on this double track. The Israeli Arik Levy is an emblematic example; he has shown specially designed pieces at many art fairs, from Fiac to Art Basel, and in 2008 at the Salone del Mobile in Milan, he presented products for no less than eight industrial companies. What has caused this increasing contamination? Is product design about usable objects or is it an art form?

“It’s undeniable that the contamination between product design and art, which were so clearly separated until a few years ago, has become more and more pronounced. As to what caused it, perhaps François Burkhardt, the noted Swiss scholar, observed correctly in his report to a meeting at ‘Abitare il Tempo’ in Verona, that it is directly due to a 'global aestheticisation' of contemporary life. What Burkhardt meant was that unlike many past epochs, today in order to ‘sweeten the pill’ of our visual (and not only visual) landscape […] the most ordinary places where everyday life goes on are being subtly infiltrated by artistic or pseudo-artistic elements.

On the other hand, Fulvio Carmagnola has noted19 that we’re turning back from the modernist mythology of functionality, to the representative and allegorical power of objects as signs, invested with an almost magical power. This very well explains the many attempts (not all of which hit their target) to create objects of daily use – furniture, furnishings, etc. – that are closer and closer to the objets d’art which at one time were kept shut away under a metaphorical glass bell, and to which were ascribed mythopoetic and magical values; but today they’re invading department stores, design showrooms, and the most advanced furniture stores. […]

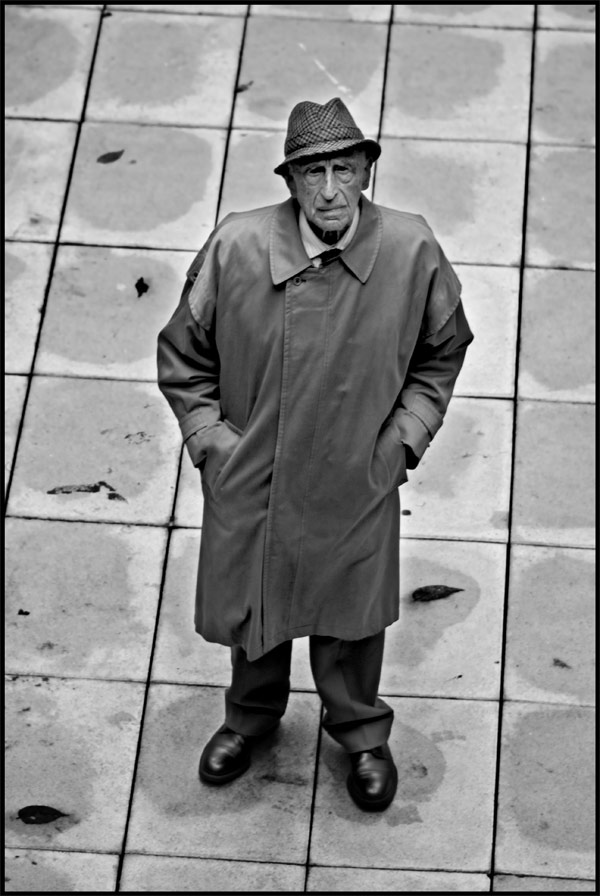

Picture by Gillo Dorfles.

Picture by Gillo Dorfles.

This trend has led to a misconception: merely playful things are considered works of art, and objects intended for everyday use have begun to neglect the ergonomic constants which, whether we like them or not, cannot be totally ignored (20)."

The fact that more and more galleries are offering artistic design is just another trick of the market. I think what they’re doing is immoral, making a work of art out of something that isn’t one. It demonstrates an increasing lack of clarity: positive values are being allowed to get confused with negative values. But there’s nothing anyone can do to stop it. When everything has to follow market values, morality serves no purpose!

As is well known, product design was the great creative adventure of the second half of the twentieth century: some of our Italian designers like Zanuso, Aulenti, Castiglioni, Mari, Mangiarotti, and Magistretti are universally considered the undisputed masters of what is really a pseudo-artistic discipline; that is, a discipline both technological and artistic. But now, not very many years since product design had its greatest successes in Italy and abroad, everyone is chasing after designer furniture, and more than often, that’s not because those doing the chasing are genuine connoisseurs, but simply because particular design objects have become fashionable.

I myself once knew a man from Versilia, a municipal health officer who, apparently very pleased, told me that when his son got married, he bought him an apartment and filled it with furniture by name designers. I thought to myself that the newly-weds’ house would surely be every bit as kitsch as the father’s own house, with its false renaissance chests of drawers and its damask chairs. Let’s not ever forget: what at one time might have been in bad taste can be adjusted to suit whatever people want. Not for the first time, satisfying popular demand can debase what was good into something that’s banal and conformist (21).”

Achille Castiglioni’s office was like a metalworker’s forge, and Frank Gehry makes card models himself, of his marvellous buildings. But there’s a new generation of designers, especially Italians, who only work on computer and refuse to’ get their hands dirty’.

There are many places in Italy where you can get excellent craftsmanship, but the relationship between manuality and industrial design is not an easy one. There’s a risk that the two might get confused; manuality might become an industrial process or vice-versa. To avoid being thought of as manual workers, some designers gradually lose contact with the materiality of their products, and leave others to produce them.

Is the “vis creativa” enjoying good health, or is there going to be a period of decadence?

“How could one deny that there’s decadence? The “vis creativa” is certainly drying up, whatever artistic field you look at: in today’s panorama I don’t see any new Joyce, Webern, or Klee emerging; only a slew of imitators, revivalists, and citationists. It seems there must be creative historical periods in which innovators bloom, and other periods of conformity when there’s a rappel à l’ordre and a return to aesthetic conservatism. It seems we’re in a period of the second type (22)”.

Italy escapes it, thanks to an imaginative streak and a freedom of invention that others don’t have. Even so, there are no Italian designers today as good as the masters were. But that’s also because the historical conditions are different. In their time, everything was being rebuilt and newly invented; in postwar Italy in the 1950s, the creative process was starting from zero and unlike other countries, there was no earlier arts and crafts movement to refer back to. The same circumstances can’t be reproduced today.

And then there’s the collapse of the universities in Italy: a general lack of rigour and discipline. When I recently gave a lecture at the Milan Polytechnic I was astonished by the level of ignorance I encountered; nobody seems to know anything, not even the basics. There are too many small schools of design springing up; we need to cut down on the number, and the ones we keep should be much tougher. They offer three-year courses that are good enough for graphic design, but not for preparing product design professionals. And the ways used to give teachers the necessary preparation are just ridiculous.

Is it possible to describe a contemporary aesthetic that includes everything going on, or is it more a matter of finding a systematisation for problematic individual manifestations that don’t fit into a single aesthetic?

In this globalised era there aren’t any rules, and there are no more groups nor even any movements. What’s most most obvious on the street is an individualistic drive to be seen, which I would call conforming to non-conformity: everyone trying to be original, doing whatever it takes to get noticed, or joining some tribe so that they can be supported by other tribe members and get recognition, for instance by wearing tattoos as tribal recognition marks.

Since we’re talking about design, we can’t leave out the Milan Salone del Mobile, the most important furniture fair in the world, which at the Fuori Salone has now also become a showcase for experimental design. Lots of people exhibit there, but many established designers have been complaining about this drift to tribalism, and are asking for the exhibitors to be pre-selected, so that the show becomes less chaotic.

At the moment it’s a free-for-all that exploits the possibility of renting old industrial buildings as exhibition spaces. The established designers have been asking for committees, so that applications from aspiring participants can be filtered. Apparently all the variety is only a disturbance.

For me, the week of the Salone del Mobile is the only time when Milan becomes a proper metropolis. I find Zona Tortona interesting, with its design events, and Lambrate too, where all the art galleries are. Those are two things that make a city come alive. The new exhibition centre at the Fiera, by Massimiliano Fuksas, is good too; it’s one of a very few interesting buildings in a city that hasn’t done anything significant in architecture since the Fifties.

As for the exhibits at the Salone del Mobile at the Fiera, and the other events elsewhere, there are good and not so good things, but that’s how it should be. The exhibits at the Fiera and the other events at Zona Tortona are the two ends of a see-saw; overall, they give a well-balanced picture. Woe betide anyone who tries to interfere with Zona Tortona by setting up a jury!

.jpg) Pictures by Gillo Dorfles.

Pictures by Gillo Dorfles.

That would take away the freedom to exhibit, from anyone who wants to. Visitors to the exhibition should learn to make their own selection of what’s good and bad. Asking for regulation is simply inviting them to be intellectually lazy – pre-processing things so that they can find their potatoes already mashed for them, and don’t have to bother exercising their own judgment. No, they must learn to see things themselves.

But can people be taught how to look?

Yes, they can, but they have to be given training. There’s a complete lack of good visual education that starts in primary school, and gets worse and worse the further you move up through the system.

So there’s a proliferation of perceptual stimulations, and a faster and faster rate of change in the arts that by now has got up to the same speed as the seasonal changes in fashion. So we’re in the same condition of everyday “Horror pleni” which, not by chance, you chose as the title of your latest book. Are we not running the risk of a dangerous sensory overload?

“It would be a good idea to distinguish between what’s excessive and on the other hand, a natural and certainly positive return that’s taking place, with the chromatisation and decoration, not only of clothing, but also in product design, furniture, and architecture. It can be explained by the natural instinct of human beings to escape the monotony of more traditional forms and colours. I think it would be wrong to deny that there’s aesthetic value in so many elements that come to us via the various media, such as advertising, television, and comic books.

In this globalised era there are no more groups nor even any movements. What’s most most obvious on the street is an individualistic drive to be seen, which I would call conforming to non-conformityIf we go back to the fundamental importance of everyday life, I still don’t think we’re paying enough attention to the particular function and importance of those things, not only in aesthetic terms, but also from a psychological point of view.

More than we did before, we now live in a condition in which the synchronic is getting the better of the diachronic; history has become the study of an academicised subject, rather than of what we are actually experiencing: very fast transformations in the arts, that we all too easily dismiss as fashion, not realising that this constant change is not only meeting an existential need of some kind, but also, I suspect, deeper needs too. You could interpret it as a real, pressing need to escape from those repetitive, relentless phenomena to which mechanisation and automation have accustomed us (23).”

There’s a relationship between fashion and design, but I get the feeling it’s viewed with suspicion. In Italy, product design has always kept fashion at a safe distance, almost as though it feared being infected by fashion’s ephemeral nature. Product designers have always considered fashion as being on a lower plane, because it has no theoretical content and is too busy trying to seduce people to be reliable or taken seriously.

There’s a new generation of product designers who are against that, and refuse to pay any attention to fashion. If they do have any involvement with the fashion world, they charge in, looking for a foul tackle (to use soccer talk) trying to subvert fashion’s rules by overlooking or deliberately ignoring the seductive side, which is actually very important when you’re designing products for everyday use. They plug their ears to avoid hearing fashion’s flattering siren song. They’re terrified of its artisan, hand-made side, its extravagance, and the way it achieves its effects so easily and superficially.

Well, product design itself is also very often in fashion itself, and therefore it has to behave in the same way as fashion. You can observe ups and downs in the success of product design that don’t happen for technical reasons, but are caused by changes in fashion. Fashion, just like product design, shares the same fundamental starting point: the project. So it’s perfectly possible to say that fashion is a branch of product design. With one difference: in product design there’s a basic, indisputable principle of functionality that fashion doesn’t have to bother about. But in fashion, you can design things that go far beyond functionality and even insult it. On the other hand, there are things that product design doesn’t need to bother with, but which are important in fashion, such as colours and textures that change with the seasons. In furniture design, there may be fabrics that go in and out of fashion, but they’re still an integral part of the furniture. Anything to do with the epidermis, in that way, is more fashion than substance, but it’s still fully entitled to be considered part of the aesthetics of the object. I don’t think fashion should be judged by the rules of product design. There’s no need to think about clothes in that way.

Well, those "sculpture and architecture” clothes do always look silly.

And so does furniture designed by fashion stylists. It’s equivocal. Fashion designers can’t possibly know what’s needed to design a piece of furniture. They just try to do it by intuition.

“It’s fairly obvious to me that product design is now partly under the control of fashion, and changes in fashion. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, and it’s equally true of all the other arts. Today everything is a literary fashion, a philosophical fashion, a psychological fashion, a scientific fashion. What does it all mean? Here we are in an epoch that seems to ensure we’re always feeling the need for our view of the world to be continually being transformed. For me, if it makes sense (even if I can’t approve of it) for product design to follow fashion and submit to its rules, then it would make just as much sense for fashion to learn from the methodology of product design, and become more serious about long-term programmatic thinking (24).”

In product design, theory doesn’t seem able to deal with rapid change, and the critical judgments that are made tend to follow old ways of thinking. They still take an exclusive attitude, whilst the media are busy making everything far too accessible to just anybody.

Current product design theory is as old-fashioned and worn out as the Bauhaus. The reality of things is different and constantly changing, but many are still stuck with the old ideas they inherited; in Italy this reliance on outdated theories is worse than anywhere else, perhaps because from the 1950s to the 1970s, Italy was the world leader in product design. We Italians are theoreticians by nature. In general, Italians lack a practical vision and don’t have an ironic way of seeing things, but among today’s critics I think Fulvio Irace is excellently balanced; he has a good theoretical base, but also understands the direct approach.

In product design there’s a basic, indisputable principle of functionality that fashion doesn’t have to bother aboutThe Compasso d’Oro, Italy’s top prize for good design created by Gio Ponti and Alberto Rosselli and promoted by La Rinascente, was first set up in 1954. Do you think it’s still in good health, or was it an instrument that no longer reflects the multiform reality of design today?

Looking back, the Compasso d’Oro prizes seem to have been fairly won and well chosen. Usually when a jury is good, they do come up with a correct selection, and they may also make enjoyable discoveries. Recently I was on a jury for the Delta ADI-FAD prize in Spain, and in Trieste, on a jury awarding prizes for the best design products from Eastern Europe. Both worked well, and the results were interesting.

Instead of ranking ugliness, I'd like to make a list with you, of the most beautiful designs.

I don’t think so, I wouldn’t be happy classifying them. In my opinion, the product designers who achieve success always cover a reasonably balanced cross-section of approaches, even though a great deal does depend on the character of the designers, and on how well they have promoted themselves.

Although the above is an unfinished mosaic that still needs other pieces to be complete, the publication dates of some of his writings already show us an emerging portrait of Dorfles as a visionary, possessed of a far-sightedness that comes from his continuous, inquisitive, irreverent observation of what’s happening around him, as he scrutinises the interstices of high and low culture, peering into the habits and manias of every type of person. Like Josef in “The glass bead game”, this enables him to see meaningful relationships between types of people who are apparently very widely separated from one another. His unusually rich conversational style ranges from the rhetorical to the vernacular, and his continually changing register moves from theoretical arguments to observations about social customs. His melodious use of the Italian language savours the full richness of the terminology he adopts, making his writings enjoyable, even at their most theoretical. The realistic approach, to which he insists contemporary criticism should adhere, is handled with great nonchalance, using a nicely-measured personal “vis ironica” that often brings a smile. He can be severe, and is always ready to issue edicts that countenance no appeal, but he is also tolerant. In these times of conformity, he has a rare, fearless independent mind.

(11). Questioni di Gusto, Ibid.

(12). Ibid.

13). Lacerti della memoria, Compositori: Boloña/Bologna, 2007.

(14). Conformisti, Ibid.

(15). Vezzi insulsi e frammenti di storia universale, Milán/Milan: Luca Sassella Editore, 2001.

(16). Horror pleni. La civiltà del rumore, Roma/Rome: Castelvecchi, 2007.

(17). Design percorsi e trascorsi, Lupetti: 1996.

(18). Horror pleni, Ibid.

(19). Carmagnola, Fulvio. Luoghi della qualità Estetica e tecnologia nel postindustriale, Milán/Milan: Domus Academy, 1991.

(20). Design: Percorsi e trascorsi, Ibid.

(21). Conformisti, Ibid.

(22). Horror pleni, Ibid.

(23). Ibid.

(24). La Moda della Moda, Ibid.

Article published in Experimenta 62 with the title Gillo Dorfles.