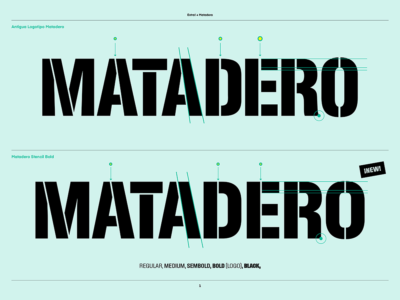

Graphic designer Leonardo Sonnoli’s (Trieste, 1962) work exudes a good deal of wisdom. His distinguished trajectory not only makes reference to his roots, but also evolves from cultural criteria. “The more you know the freer you are to generate ideas.” An author that shies away from the prospect of coining a style of his own through his posters but who accepts and even defends their minimalist approach: “The fewer elements you use the faster and more direct the communication you achieve.”

Leonardo Sonnoli has participated in various poster biennials and triennials the world over, both as a contestant (receiving numerous awards for his designs) and as a member of the jury. Posters, thus, occupy a place in their own right within the body of his work, and not necessarily on account of their showing signs of a style that is more personal than the one evident in the rest of his daily professional activity, but owing to the fact that posters truly form part of his artistic life, as well as of his design principles.

This situation, which is by no means exclusive to Sonnoli, is, notwithstanding, important when it comes to looking for a key to decipher his oeuvre, i.e. moderation. By moderation we mean the care he has always taken to express himself with absolutely pertinent, necessary and competent strokes in order to ensure that true communication takes place, without this entailing a denial of the vibrations that emanate from the meanings being transmitted; a connotative capacity which, avoiding out of place sentimentalism, we could very well define as poetic. This adjective, in effect, denotes the possibility of polysemous expression, which in this case is not detrimental to the objective of the message.

In the first place, moderation is born out of the formal tools put to use by Sonnoli: tools given over to clarity, but which do not fall into the ideological trap of translating clarity into order, geometry or regularity. The eye does not see as a result of the mathematical laws which geometry makes perceptible – a hypothesis endorsed in the 20s by the writings of the psychologists from the Berlin Gestalttheorie, and to a certain extent betrayed, perhaps, by the Functionalist line which extended from the Bauhaus to the Swiss School (and from which we have consciously excluded Constructivism).

Rather, this clarity is born out of an unequivocal evaluation of the elements that make up the graphic structure of a “page”, in the widest sense of the term. Hence, the consistency between image and text is fundamental (a reference: László Moholy-Nagy’s Typophoto). However, a designer’s task today is more complex than in the days of the Hungarian master: the challenge of striking a balance (harmonious and discordant, depending on the message) between the two always in effect. Turning to a metaphor, it is, perhaps, the relationship between communication and information set forth by the Ulm Hochschule fur Gestaltung in the 60s, sought by the Kinetic Art movements with their derivations towards graphic design. A name among them: that of the Italian Franco Grignani, whose visual experiments were turned into a manifesto.

Sonnoli’s work takes up this challenge with a dose of originality: lettering, the pillar of graphic work, wields the power of evocation with moderation, i.e. it does not fall into an excess of expressivity, but limits itself to suggesting the possible semantic vibrations of the subject to which it refers. While the image, on the other hand, sees its potential visual impact reduced, finding in moderation a way to suggest, rather than state, a message. The spectator stares on speechlessly, realising all that must be looked into in the relationship between these two features. But it is precisely in the fine articulation between image and text where we often find the stroke that gives away professional mastery. And there is something else. This approach makes it possible to sidestep the idea of personal style, which does not befit a designer – as a professional given over to alien objects – and, on the other hand, it underlines the existence of a “meta-stylistic” approach, a kind of style of design, which is noticeable in the way problems in the visual milieu are solved.

Finally, this way of understanding communication is also symptomatic of an ethical posture when it is redirected to the sphere of professional, in addition to political, consciousness, since Leonardo Sonnoli is the Chairman of the Italian branch of AGI (Alliance Graphique Internationale), and one of the few Italian designers renowned throughout the world. A stance against a visual contamination that is made up of “screaming” colours, of redundant iconographies, of stolen stylistic traits, which invariably form part of our “image civilisation”. But perhaps the term “against” is excessive, because, once again, Sonnoli turns to moderation, avoiding an unnatural radical posture in his search for intelligent solutions. In other words, a design-based attitude.

Article published in Experimenta 55.